Innbyggere I den parisiske forstaden Gennevilliers kjøler seg ned under hetebølgen I 2020. Fontener tilkoblet brannhydranter er en del av kommunens beredskap for å dempe de skadelige følgene av hetebølgen, og skape tilfluktsteder for de som ikke har tilgang til aircondition eller andre muligheter for å kjøle seg ned. (foto: Ville de Gennevilliers / flickr)

The heat is here to stay

Europe is warming faster than the global average, and has seen a dramatic increase in the number of heatwaves over the past 40 years. This trend will likely continue, even with major reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

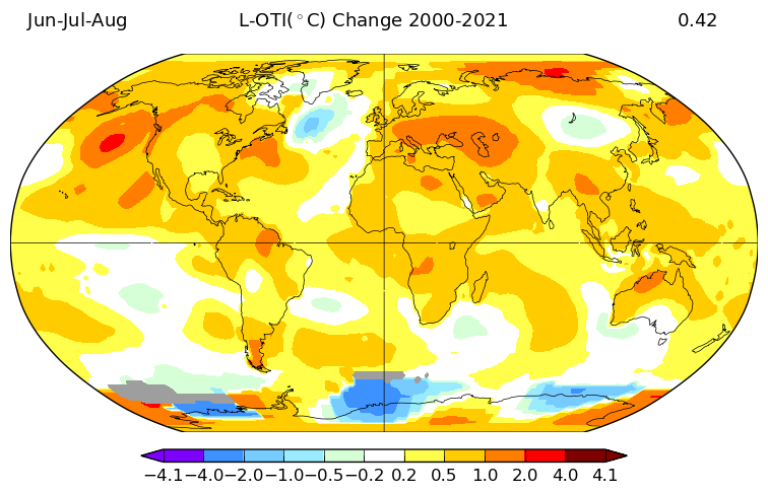

Since the Industrial Revolution, the global temperature has risen by around one degree, but this is an average figure; the whole world does not warm at the same speed. Europe is warming faster.

'Europe is warming faster than average, largely because land areas warm faster than the oceans,' says Kalle Nordling, a climate modeller in CICERO.

‘Europe is also warming faster than several other land areas on the planet,' he points out; 'And it's the summer temperatures that stand out. Those temperatures have risen a half degree faster than the global average for the period 2000–2021.'

According to the climate models, even if we manage to reduce greenhouse gas emissions enough to limit global warming to almost 1.5 degrees, warming in Europe may still exceed 2 degrees.

In the summer of 2020, Europe was approximately 2.5 degrees above the pre-industrial average. In other words, this may foreshadow a new normal by the end of this century.

Changes in the jet stream

Over the past 40 years, Europe has seen a steep increase in the number of heatwaves compared with land areas at the same latitude. The connection between a higher average temperature and heatwaves is not a given, however; in some places global warming will lead to wetter and more humid conditions, not necessarily searing desert heat.

Across Europe it seems that higher ground temperatures create atmospheric conditions that can trigger heatwaves: ‘Global warming can affect atmospheric streams, for example by affecting the way in which the jet stream behaves,' says Nordling.

The jet stream is a band of wind found 5–15 km above sea level that flows around the northern hemisphere. In a recently published article, researchers at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) linked the increase rate of European heatwaves to changes in the jet stream.

Sometimes the jet stream splits in two and creates an area of high pressure and little wind between them. Similar conditions have coincided with several of the European heatwaves, including those that occurred this summer,' says one of the researchers behind the article to The New York Times.

According to the article, a higher average temperature above land in the northern hemisphere may cause such atmospheric conditions to occur more frequently, last longer, and create more heatwaves.

The article points out that climate models do not recreate such changes in the jet stream in a satisfactory way, and that for this reason we may end up underestimating how common heatwaves may prove to be in future.

According to Nordling, we will probably have to get used to heatwaves in the coming years, especially if we fail to reduce greenhouse gas emissions: 'The consequences of continued warming will be more intense and more frequent heatwaves, prolonged and more intense droughts, and higher mortality rates," he says.